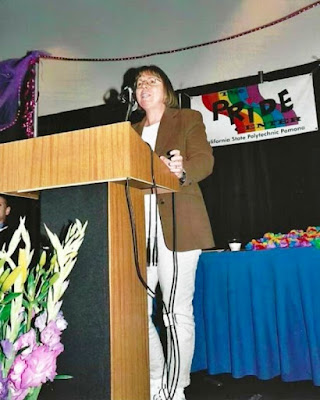

Monika: My guest today is Claudine Griggs, an American writer and college writing instructor. She earned her BA and MA in English at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, and she has worked as the Writing Center Director at Rhode Island College and as a visiting professor of communication skills at Soka University of America.

She is currently a part-time writing specialist at the Bush School of Government and Public Service in Washington, D.C. Claudine is known for her science fiction stories, including "The Cold Waters of Europa," "Growing Up Human," "Firestorm," "Maiden Voyage of the Fearless," "Death after Dying," "Informed Consent," "The Gender Blender," and "Raptures of the Deep."

One of her stories, "Helping Hand," was selected for The Year's Best Military and Adventure SF 2015 and was adapted as an episode in the Netflix series Love, Death and Robots. Her most recent book, Firestorm, a collection of twenty-three of her short stories, was released in March 2022. Her novel Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was published in June 2020.

Hello, Claudine! I am so happy that you have accepted my invitation!

Claudine: Thank you. It was a pleasure to hear from you.

Monika: You are a very prolific writer. What do you think makes a good story?

Claudine: If I knew the precise answer, I’d probably write more stories like “Helping Hand.” But it’s difficult to predict what will interest a publisher or a producer, so I focus on creating stories that interest me.

The most important aspect is the narrative itself. I know that character is important, too, but for me the story carries more weight. I love journeys and optimism along with a bit of the heroic. I also think that humans are a pretty good species, overall, and I often reflect this in my work. And if narrative surprises happen along the way, even better. But again—story, story, story.

Monika: The majority of your books are science fiction. Is that your favorite genre?

Claudine: Actually, I have three nonfiction books in addition to my fiction. My first book was Passage through Trinidad: Journal of a Surgical Sex Change (1995); the second, S/he: Changing Sex and Changing Clothes (1998); and a quasi-third was an expanded edition of the original Passage through Trinidad that appeared in 2003 as Journal of a Sex Change. However, science fiction is underappreciated in academia, so when I was teaching, I leaned toward writing academic nonfiction out of necessity. But in 2009, I decided it was time to re-engage with my first-love genre and began writing speculative stories. My first SF publication was “Firestorm,” which was followed by several others.

I believe that my previous academic publications helped a little when I ventured into fiction, but the genres are very different, and one field doesn’t necessarily offer bonus points with editors who work in another. Thus, I received many, many rejections among only a few acceptances during these early years.

Then, in 2015, “Helping Hand” was accepted by Lightspeed magazine. Very nice! Soon, there came an offer to reprint this story in The Year’s Best Military and Adventure Science Fiction. I figured life couldn’t get much better than that. Then Netflix asked to include the story in their upcoming Love, Death & Robots series.

I sometimes wonder if this marks the peak of my writing career, but I keep writing and submitting. There are still lots of rejections along with a sprinkling of acceptances to help keep me going. My first novel, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, a suspense/mystery/thriller was released by Not a Pipe Publishing in June 2020. And Firestorm, a collection of 23 of my short stories, was published in March 2022 via Ananke Press. With any luck, I expect another SF book called Desperate Moon to be out in 2023. So, yes, science fiction is my favorite genre. To me, it’s the genre of hope.

Monika: Your first book “Passage through Trinidad” was a vivid account of your sex-reassignment surgery. When I had mine, I was euphoric but somehow wanted to forget about the surgery itself as soon as possible. In your case, you did not forget anything, and on the contrary, you were meticulous about describing it.

Claudine: These days, my Trinidad Experience lives in a galaxy far away and long ago. I can’t imagine my life without having had genital surgery, but before I found Dr. Stanley Biber in Trinidad, Colorado, I wondered if I would ever locate a qualified surgeon to assist me. This was no easy task in the United States in the 1970s and 80s. After several years and many failed attempts in search of treatment, I essentially gave up, deciding to live as best as I could without surgery while continuing hormone therapy. Not what I wanted but better than trying to exist as a man. Ugh!

When I finally obtained gender-affirming surgery, the physical and emotional trauma surprised me, so I started writing “Notes on a Trip to Trinidad” for my personal record as soon as I returned to California. I thought this would be 20-30 pages at most, but the more I wrote the more I wanted to write, and the document ended up at about four hundred pages. It’s as accurate as I could make it, and I seemed to have a near photographic memory (which I’ve not had before or since) of the daily hospital routines and conversations.

I think Passage through Trinidad is overly detailed, but it was the descriptive detail that seemed to most interest the publisher. Still, even after I received the offer of publication, I hesitated for several weeks to sign the book contract. Part of me wanted to leave the experience behind and try to disappear into life as a woman. I was also afraid of coming out as trans in 1991. The closet seemed much safer.

Monika: How did you find out that gender reassignment surgery is possible?

Claudine: I didn’t have “gender reassignment” surgery. I modified my body to support my gender identity. Many people don’t distinguish between gender and sex, but that distinction is vital in understanding gender identity conflict. That’s why I typically use the term transsexual though I know transgender is the more popular term these days. In any case, I reconsidered genital surgery at the suggestion of my long-term endocrinologist with whom I’d been working from 1974 through 1990.

At one of my regular medical checkups, he asked, “Why haven’t you had surgery?” I explained my early efforts and many failures, including the surgeon who lost his medical license a few weeks before I would have otherwise gone under the knife. My doctor’s response in 1990 was, “The dark days of trans-medical treatment have passed. You can obtain surgery safely now.” This conversation led me along a circuitous route to Dr. Stanley Biber in Trinidad, Colorado. I remained skeptical but moved forward.

Monika: Dr. Stanley Biber has become a legend among the US transgender community. He is said to have performed more than 2,300 male-to-female genital reassignment surgeries. How do you recall him?

Claudine: According to the Los Angeles Times obituary, by the time of his death, Dr. Biber had performed over 5,000 MTF surgeries and over 800 FTM surgeries. I read somewhere else that the number exceeded 6,000 in total. What I’m sure of is that on July 24, 1991, he performed one MTF surgery on me, and I am reverently grateful.

I met Biber at a time when I mistrusted most of the medical profession, yet Biber seemed like a good old country doctor who actually cared about patients. And he was imperiously confident in his skill, which was exactly what I needed at the time. I had been terrified of some of the physicians I’d met in past years and worried that they might kill me on the operating table through incompetence. I once said that Biber seemed a mixture of Huck Finn and Genghis Khan. Just what I needed to prevent a complete emotional meltdown at the time.

|

| "Many people don’t distinguish between gender and sex, but that distinction is vital in understanding gender identity conflict." |

Claudine: I don’t know all the details, but the “Sisters of Charity” helped to run the hospital, and I was originally referred by my endocrinologist to a Catholic nun who then referred me to Dr. Biber and Mt. San Rafael Hospital. This concerned me, initially, because “Christian” folks often seemed to have distinctly un-Christian attitudes toward me in the 1970s and 80s after I changed my name from Claude to Claudine. But at this point in my life, I would have accepted help from Satan, himself, if help were available. However, once I arrived in Trinidad and met the hospital staff, I was forced to question my own prejudice against religion. “Maybe,” I thought, “some of these people really are good.”

Monika: Dr. Biber used to perform 4 surgeries per week. Did you have a chance to make friends with other girls at the hospital? Do you still keep in touch with them?

Claudine: The week I was there, Biber did three MTF surgeries. At first, I didn’t want to maintain contact with the transwomen I met in Trinidad. I wanted to go home, forget the experience, and resume my “normal” life as a legal secretary in Southern California. But within a few months of my recovery, I decided to write to my Trinidad trans-associates. I still correspond with “Virginia,” whom I mentioned in Passage through Trinidad, but I lost contact with “Georgina,” who continued to suffer from depression and ultimately de-transitioned. I hope she’s OK but worry that she may have committed suicide. Hope I’m wrong. But Virginia and I usually talk with each other on the anniversaries of our surgeries. She’s happily married and doesn’t want exposure as a transwoman. I sometimes wonder whether she chose the better path.

Monika: Do you have any regrets in this respect? It is fantastic to leave the past behind and be a woman, wife, or mother and be addressed without any preceding adjective such as 'transgender' or 'transsexual' but keeping such a secret may be very burdensome...

Claudine: I often wonder how my life would be as a “normal” woman, and sometimes I wish I had tried to disappear after genital surgery, maybe get married, and hide the fact I’m trans. But for me, that didn’t seem realistic. First, I was born in Tennessee, which prohibits trans folks from changing their birth certificates to reflect a new sex.

Second, I’m not very good about hiding my past, and upon some reflection, the surgery made it easier to admit my trans-status. Third, I learned that keeping such a secret, as you say, is burdensome, and I began to enjoy letting go of that. But, yes, sometimes when I talk with Virginia, I wish for a life where only close family knew I was trans. Of course, if I were going to get a wish, I’d prefer to have been born female. And since I can’t have that fantasy, I do the best I can. And things turned out better than I expected.

Monika: Do you remember the first time you saw a transgender woman on TV or met anyone transgender in person?

Claudine: I read an article about Christine Jorgensen when I was in high school but found it confusing. It didn’t seem that a biological male could be so thoroughly transformed, so I assumed Christine was an intersex person who had a feminine tune-up. Later, when I realized that transsexualism existed and could be treated, I remained skeptical about my own feminization, so I started reading more to examine possibilities. Eventually, depression drove me to a psychiatrist, which led me to seek help with my gender dysphoria.

Monika: Were there any transgender role models that you followed?

Claudine: In the early 1970s, there were no trans role models that I know of, and I didn’t knowingly meet another transwoman until my second year of transition when I visited a potential surgeon in Compton, California. But I had lots of women role models. Mostly, I knew that I wanted to go to college, graduate, and work my way into a profession. I also hoped to get married someday but didn’t think my chances were good in this area.

|

| "I had lots of women role models. Mostly, I knew that I wanted to go to college, graduate, and work my way into a profession." |

Monika: What do you think about the present situation of transgender women compared to what you had to go through yourself?

Claudine: I’m very pleased that transmen and transwomen have access to better and safer medical care and that health insurance covers many of the costs. In my day, finding care was next to impossible, and then one had to pay cash upfront for any treatment. I’m also pleased that children can obtain medical care before adolescence. This seems especially helpful for transwomen because a male puberty wreaks havoc on their bodies.

Monika: When I look at our younger sisters, I am quite jealous about two things: support from parents and puberty blockers...

Claudine: I lost my entire bio family when I transitioned; decades later, my parents learned to tolerate me, and later still, to quasi-love me but still as their “son.” Parental support for a transitioning child seems one of the best overall improvements. Also, the post-transition results are typically improved when gender-contradictory puberty can be halted. I will never look completely female; I will never sound completely female; I will always see “male” in me, and I hate that. It's nice to see parents supporting their trans-children. In my day, parents and extended family would double down on role training according to birth sex, which was torture.

Monika: We are said to be prisoners of passing or non-passing syndrome. Although cosmetic surgeries help to overcome it, we will always be judged accordingly. I have always been struggling with this myself. Did you have to cope with this as well?

Claudine: I continue to judge myself by how feminine I look or don’t look on a given day. When I go to the store or anywhere in public, I sometimes still feel surprised when people address me as “ma’am.” Even after almost 50 years of life as Claudine, I half expect to hear “sir.” When I see a naturally feminine woman, especially if she’s pretty, I often feel deformed.

Monika: What would you recommend to all transgender women that are afraid of transition?

Claudine: I think it’s reasonable to have some fear about body and social modifications on this scale, and I hope that transwomen would seek professional medical counseling and care. Doctors and therapists are much better informed in 2023 than 1973, which should help to comfort those seeking to transition. All change can be disruptive to some degree, and changing the public expression of one’s gender identity is a big deal.

Monika: My pen-friend Gina Grahame wrote to me once that we should not limit our potential because of how we were born or by what we see other transgender people doing. Our dreams should not end on an operating table; that’s where they begin. Do you agree with this?

Claudine: Yes and no. The way we’re born affects our lives, and transwomen have a bodily reality that cannot be ignored. For me, changing “attributed gender” (the way I was perceived by others) was beneficial, but it didn’t solve all problems. Nothing does. We still have whole lives that don’t begin or end with hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgeries. For some, the best possible life may include sex reassignment. But “life” is our real business.

Monika: Claudine, it was a pleasure to interview you. Thanks a lot!

Claudine: Thank you, too. I wish you and your audience all the best!

All the photos: courtesy of Claudine Griggs.

© 2023 - Monika Kowalska

I LOVE having finally found Claudine's story online. I bought and read, reread and reread "S/HE". And, am a fan of "Love,Death and Robots". I'll have to pursue more of her Sci-Fi writing.

ReplyDeleteI am a cis-male, but exist on the trans spectrum and am appreciative of this interview. Thank you.

Hi, Richard: Glad you like S/HE, which is one of my favorite books. Claudine Griggs

Delete