It is not every day that you encounter a woman whose words can move mountains, whose journey carries the weight of generations, and whose courage unfolds line by line in verses both tender and unflinching. Barbara Marie Minney, a seventh-generation Appalachian and native of West Virginia, is one such woman. Now living in Tallmadge, Ohio, she is an award-winning poet, writer, speaker, teaching artist, and quiet activist. Her work has been featured in Politico, The Buckeye Flame, Gargoyle Magazine, The Gasconade Review, and numerous anthologies amplifying female and queer voices, including Woman Scream: The International Poetry Anthology of Female Voices. Barbara is the author of four powerful poetry collections, including If There’s No Heaven, winner of the 2020 Poetry Is Life Book Award.

A retired attorney with a distinguished 36-year legal career, Barbara now devotes herself to writing poems that reflect her life as both a transgender woman and an Appalachian storyteller. Her voice, shaped by years of personal searching and spiritual resilience, is personal, raw, and deeply human. In today’s conversation, two women sit down, one a blogger and interviewer, the other a poet and quiet revolutionary. We talk about poetry, the long road to womanhood, the bittersweet aftermath of transition, and the tension of inhabiting identities that don’t always fit into simple categories. Barbara and I meet not just as interviewer and guest, but as sisters in experience, exchanging reflections that come only from living a truth that had to be fought for, sometimes silently, sometimes in verse, but always bravely. Let’s begin.

Monika: Hello Barbara! It's not every day I get to meet a poet. What a treat!

Barbara: Hello, Monika! Thank you so very much for this opportunity to be interviewed by you. I have been looking forward to it since you first contacted me.

Monika: Would you say being a poet in the 21st century comes with unique challenges, or is it still the same old struggle for recognition and readership in a digital world?

Barbara: Being a poet in today’s world can be very difficult and frustrating, but it can also be very rewarding. Unless you are one of the top-echelon poets like Rita Dove or Joy Harjo, you are pretty much on your own insofar as publication, promotion, and obtaining recognition are concerned. This time last year, I felt that maybe I was on the verge of a major breakthrough when I signed a publishing contract with a company located in Chicago. However, those hopes were dashed when the contract was canceled about a month and a half before the manuscript was due to be delivered. That was devastating. I was left with a manuscript but no publisher.

Only small publishers are interested in your work if you are not a well-known poet, but I have been very lucky to have made some contacts in the publishing world. My poems have been published frequently in anthologies, and recently some of my poems were translated into Spanish. I have had two publishers express an interest in publishing separate chapbooks this year, so in the end, the cancellation of my publishing contract probably will turn out for the best. However, I am always looking for ways to take my poetry to the next level. I consider it a kind of ministry.

|

|

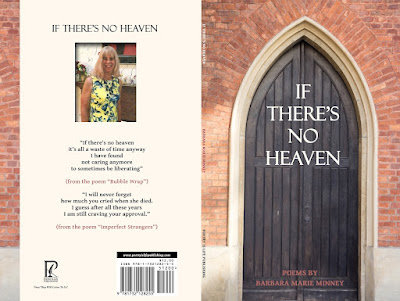

"If There's No Heaven" was the winner of the 2020 Poetry Is Life Book Award. Available via barbaramarieminney. |

Monika: That was beautifully expressed. It sounds like your journey as both a writer and a transgender woman has been deeply intertwined. How have you come to navigate the tension between being seen as a poet who happens to be trans and embracing the label of a transgender poet?

Barbara: When you suffer from depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem, like I have most of my life, you do not always recognize your own self-worth and the effect and impact that your work has on others. Early on, my work seemed to be more popular with the cisgender community than the LGBTQ+ community, and to a large extent, that is still the case. The audience at my readings is almost entirely made up of cisgender people. I think that speaks to the universal themes that permeate my work, even though I am writing from the viewpoint of a transgender woman.

I have always identified myself as a transgender woman, even at my very first readings. However, I frequently struggled with the question of whether I should run away from, or embrace, being identified as a queer poet and writer. I wondered if the success that I have had as a writer and poet is because I am somewhat of a novelty as a transgender woman who happens to write poetry and essays, or because I am a truly talented writer. I answered this question for myself in an essay entitled “I am a transgender poet. Not just a poet. And that label is important,” that was published in The Buckeye Flame, which is Ohio’s weekly LGBTQ+ publication. I conclude the essay by saying, “If the label transgender or queer writer or poet limits me, then so be it. That is who I am".

Monika: You began writing poetry nearly 40 years ago, but then stepped away from it for a long time. What led you to stop writing, and what eventually brought you back to it?

Barbara: That is correct. I wrote poetry and short stories in the 1970s for my college literary magazine, and I did win some awards. I even had a poetry reading. For a brief time, I considered pursuing a career as a writer. However, after college, I stuck with the plan that I had formulated in third grade when I read a book about Abraham Lincoln. I attended law school and embarked on a thirty-six-year career as a high-profile attorney in my area of practice. During that time, I did not write another word except for three legal books that I co-authored. The work was stressful and all-consuming, and I was able to walk away at the age of sixty.

When I retired in 2014, it took me a very long time to adjust. I was dealing with the illness and eventual death of my father, and I turned back to writing as an outlet. I first wrote an erotic novel, which the publisher liked but wanted me to add another six thousand words. That is when I realized that my genre is poetry, and I began writing my first book, which was autobiographical in nature. It chronicled my first two years living as a woman after transitioning at the age of sixty-three. Writing helped me process the changes that I was going through both physically and mentally.

|

| "I have always identified myself as a transgender woman even at my very first readings." |

Barbara: As I said, poetry has always been my genre going back to when I was a freshman in college. I did not think of my book as a memoir until very recently, but that is exactly what it is. My second book is actually called the Poetic Memoir Chapbook Challenge.

As Hemingway suggested, I write about what I know. I may be naive, but I rarely hold anything back in my writing. My main themes are being a transgender woman and being a seventh-generation Appalachian. I try to make my poetry accessible, and it has been described as personal, raw, emotional, and authentic. I share my story through my poetry and try to portray a positive image as a transgender woman, but at the same time, I do not hesitate to share my struggles as well as my triumphs.

Monika: Looking back, would you say your childhood was a happy one? Or were there early signs of the inner conflicts you would later come to understand more fully?

Barbara: This is a very hard question for me to answer. I will just say that I did not have an unhappy childhood. Unlike a lot of transgender individuals, I do not remember feeling at a young age like I was in the wrong body or the wrong gender. I did typical boy things like play sports and go fishing, and I was very interested in music. I played in school bands through my sophomore year of college and had a little group in high school modeled after Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass.

I did spend a lot of time alone either reading or making up games with my baseball cards, and I enjoyed interacting with the neighborhood girls. I was groomed to be successful in academics and a career. I learned to be very goal-oriented and a perfectionist, and that probably led to a lot of unhappiness throughout my life.

Monika: You had a remarkable and successful career as an attorney. What was that chapter of your life like, and how do you reflect on it now?

Barbara: Yes, I was very lucky in my career. I started as an assistant prosecuting attorney and became a partner in two different law firms. However, my work was very challenging and demanding. I represented public school district boards of education, which was often very high profile, and the clients were very challenging.

I remember very little about the thirty-six years that I practiced law, except for the work itself. It was pretty much all that I thought about. I still have dreams about various phases of my career. I did indeed rise to the very top of my chosen specialty and often spoke on a statewide and national level, but it also took a toll on my mental and physical health.

Monika: Based on my own experience, and after speaking with so many other women in our community, I sometimes feel we should be called "runners" rather than trans women. We spend years running from our feminine selves until, eventually, she catches up to us. The only real difference is how long each of us can keep running. Did you feel that same kind of chase in your own life?

Barbara: This is a very perceptive and important question, and the answer is yes. I repressed my true gender identity for over sixty years. I had no idea who I really was until I found a counselor who literally saved my life, or at least, helped me find it.

I experimented with crossdressing in my teens and went through many periods of obtaining clothes and magazines about gender issues. Then I would purge and eventually start over again. Eventually, when my wife was out of town, I went on a personal odyssey. I “met” another crossdresser online who lived near us, and we had a lengthy conversation. When I returned home, I had a conversation with my wife and told her that I could no longer suppress my feminine side.

That same week, my wife and I happened to meet my new crossdresser friend and her wife at an event, and they invited us to a monthly girls' night out that was held in a gay bar nearby. The first time I attended, I looked hideous by the way. That was our first real exposure, and I think that my wife was comforted by the fact that there were other spouses and significant others that she could talk and relate to. We began doing research and reading books and other materials and attending support groups. That was really the beginning of my journey to living as the woman that I now know I was always meant to be.

|

| "I definitely lost friends, acquaintances, and social standing when I transitioned." |

Barbara: I try very hard to avoid talking about politics. I have always been right of center politically, but my beliefs are evolving. I am more of a libertarian. I transitioned late in life when most of my core values had become ingrained. It is not so easy to trade in a viewpoint accumulated over a lifetime for a way of thinking that you are told you should have by the more vocal and activist members of the new community that you have suddenly become a part of. I think that the fact that there are indeed many more conservative leaning members of the LGBTQ+ community is an indication that trans people aren’t just an interest group. We’re complicated, multi-faceted people.

Monika: In your journey, has faith, or perhaps being part of a spiritual community, played a role in helping you cope with dysphoria and find self-acceptance?

Barbara: I do not necessarily like the word “religion.” I much prefer the word “community.” I would not say that finding a spiritual community helped me tackle dysphoria, but it certainly helped. However, I would most definitely say that the community that we ultimately found did help me accept myself and recognize my self-worth.

I have always been a spiritual person and did a lot of exploring of alternative spiritual practices and beliefs. However, I rejected organized religion for almost thirty years. It was about three years ago that my wife and I started to explore the possibility of once again becoming a part of a church community, but it took us some time to find the right fit. I have always considered myself to be a Christian, and I am an administrator of the Transgender Christian Facebook Group.

Our first attempt at finding a spiritual community was a failure, so we started another search. That led us to the Harmony Springs Christian Church, which is affiliated with the Disciples of Christ. We became members after attending for a year online during the pandemic. Our church is for spiritual refugees, who have given up on church. It is radically inclusive. My wife and I both have leadership positions in the church, and I have spoken and read my poetry during several church services. I was even re-baptized as Barbara in a service that was totally structured around celebrating me. The pastors and members of the congregation have been extremely welcoming, supportive, and encouraging, and it is something that we really need in our lives right now.

Monika: Many of us pay a steep price for the freedom to live as our true selves—losing family, friends, jobs, or social standing along the way. Did you face such losses in your own journey? And what would you say was the most difficult part of coming out for you?

Barbara: My transition was very public. I agreed to be interviewed in the local newspaper about my experiences with gender counseling. It was a big multi-page article that included two pictures of me. I received two kinds of comments about the article – how brave I was and how much leg I was showing in the pictures.

I definitely lost friends, acquaintances, and social standing when I transitioned. We were no longer able to participate in some of the groups to which we had belonged. I had already retired from my position as an attorney when I transitioned. However, I was still doing some consulting work, and I was removed from the firm’s website. Both of my parents were already deceased. I have one brother who I have not seen for almost five years.

|

| "I waited until my parents were both deceased before I transitioned, so they never knew Barbara." |

Barbara: The name Barbara was chosen for me. During my crossdressing period, we occasionally got together with another crossdresser and her wife. It was the wife who dressed me up one evening and said that I looked like a Barbara. I really liked the name and stuck with it when I transitioned. I think that it is elegant, classy and age appropriate. And, it has to be “Barbara” not “Barb.” I have always liked the name “Marie,” because it sounds French. I am somewhat of a Francophile, so I used that as my middle name.

Monika: Did your family ever know about your transition, or were they surprised when you came out as Barbara? How have your relationships with family members evolved through your journey?

Barbara: I waited until my parents were both deceased before I transitioned, so they never knew Barbara. I really have no idea how they would have reacted, but I don’t think my father especially would have been too accepting. I really have no other family, except one brother and some cousins that I have not seen for years. My brother saw Barbara one time when my wife and I renewed our vows and remarried as two women. That was almost five years ago.

Monika: Are you satisfied with the results of your hormone treatment, or do you find yourself still wrestling with aspects of your appearance?

Barbara: I am not sure that I will ever be totally satisfied with the way that I look. I am my own worst critic and can always find some fault when I look at myself in the mirror. I want to look as feminine as I possibly can, and I will always have some dysphoria related to certain parts of my body. Having said that, I would say that I am mostly satisfied with the effects of the hormones.

END OF PART 1

All photos: courtesy of Barbara Marie Minney.

© 2023 - Monika Kowalska

No comments:

Post a Comment